J Davies: Kia Ora!

September 28th, 2024

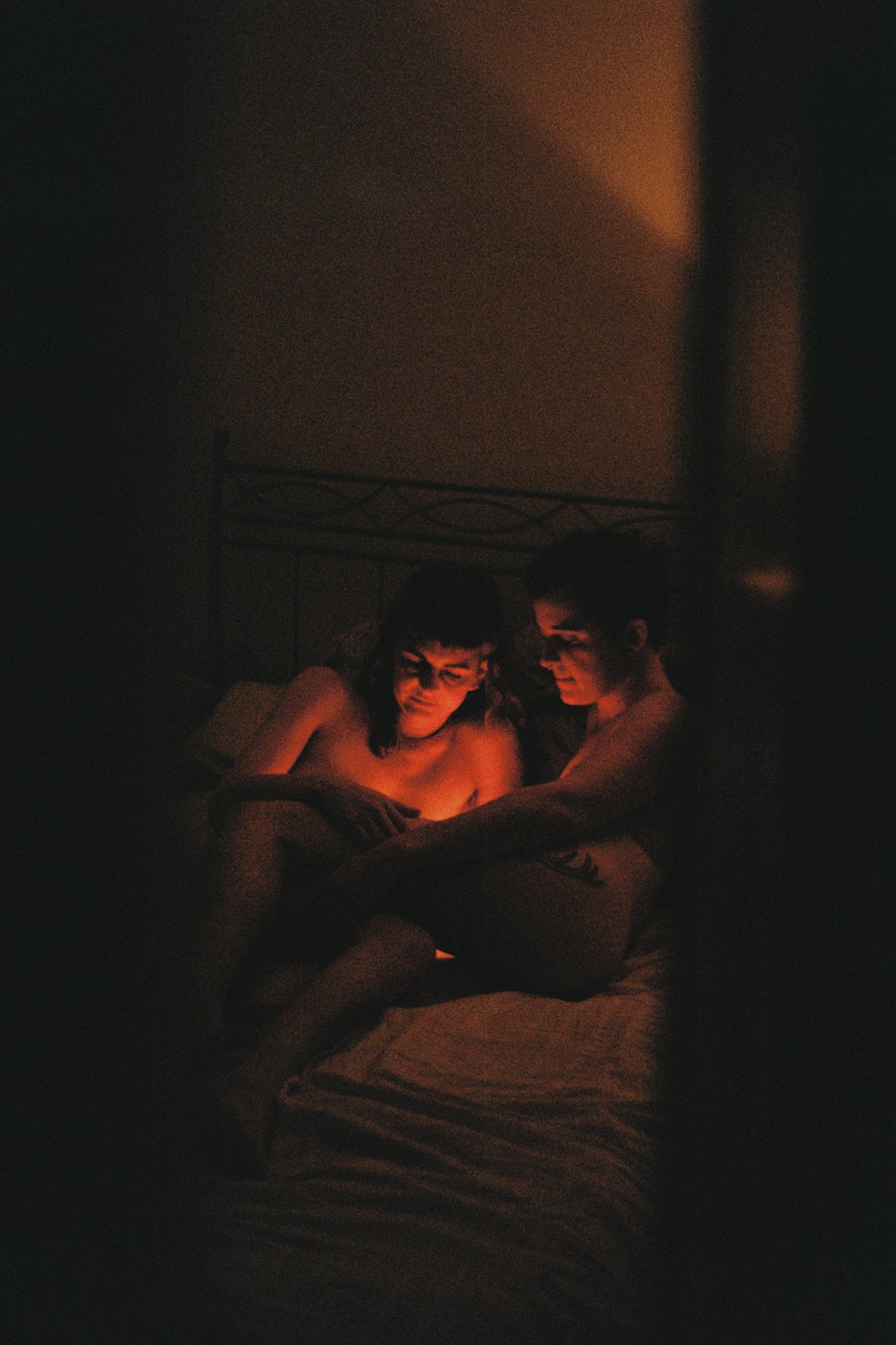

When you encounter J Davies' work, you immediately feel the personal and political layered into every frame. J’s practice spans photography, video, and installation, but it's their dedication to analogue film that stands out. Shooting exclusively on 35mm, medium format, and Polaroid, J captures the fleeting, intimate moments of queer life—moments that feel both timeless and achingly present.

From early experiments with disposable cameras to a now established practice, J's relationship with photography has always been about process and authenticity. Their commitment to film forcing them to slow down, to embrace the unpredictability of analogue, and to let the work unfold naturally—scans are either a hit or miss, but that’s part of the appeal. It’s this hands-off approach, coupled with a deeply personal perspective, that makes their images feel like more than just photographs—they're a living archive of queer experience, meant to be seen both today and for decades to come.

We caught up with J, deep diving into their work and taking a look at inspiration, meaning, subjectivity, and photographic creation:

POL: Hi J! To start off can you introduce yourself and your work for our readers?

J: Tēnā koutou katoa! Hello! I’m J Davies, an Australian born takatāpui (Queer, Trans, Māori) artist utilising photography, video, sculpture/installation and words. I’m currently living and working on the stolen lands of The Kulin Nation in Naarm (Melbourne, Australia).

POL: What was your first introduction to photography?

J: From memory, the first camera I would have been gifted would have most likely been a disposable camera (35mm) for grade 5 camp in 2004. By the age of 14 I was taking acceleration photography classes in high school and was given a Sony Alpha DSLR for my birthday.

I dabbled in digital photography for a while but I was always more interested in film. Throughout my teen years I was buying disposable cameras from the reject shop and using cheap plastic lomography cameras. Never knowing what you’d get back from the developers kept me on my toes - it was like Christmas every time I got my scans back (and still is).

POL: Do you remember the first shoot you were really happy with?

J: I don’t know if there was a specific shoot that stands out but some of my early teen party shots still hold up. Lots of double exposures with coloured flash with perspex lens filters and image distorters. I don’t know if I still have access to them anymore though. They may have gotten lost on one of my many broken hard-drives.

POL: You say you’re drawn most to analogue photography, do you think this is an aesthetic or more of a technical preference?

J: All of my photographic work is taken on either 35mm film, occasionally medium format, or polaroid/instant film. I sequence digital handycam footage for the video works I make but that’s the only digital image maker in my tool box.

Initially there was part of me that was drawn to the aesthetic qualities - the romance and nostalgia of the past. Early in my life I was inspired by family photo albums and I think that aesthetic association to the progression of time has carried through into my contemporary practice. Film also encourages me to slow down and be more decisive. I don’t edit any of my images, whatever scans come back are either usable…or not.

POL: We’ve read that your work has been described as “archiving contemporary queer existence”, and we’re interested in that phrase as the idea of an “archive” in popular consciousness tends to be racks of cardboard boxes, and the historical. What does the phrase mean to you?

J: A lot of the artists that have influenced and shaped my practice created archives of their queer family of friends throughout different decades. Although I am making work to be shown today there’s also a big part of me that's creating this work for audiences in 20-30 years time. We are preserving our lives for future generations of queer people to see how we looked, how we lived and how we loved.

“We are preserving our lives for future generations of queer people to see how we looked, how we lived and how we loved.”

If we don’t tell our own stories the way we want them to be told, who knows how they’ll portray us. This goes for all marginalised communities who have had their stories erased, or obscured, throughout Eurocentric history.

POL: Off the back of that, do you feel a social/political responsibility for how and what you produce? Especially if you’re producing images with an intent for documenting and storing significance?

J: Hmm…sure, there’s an element of pressure in establishing an ongoing archive of what my queer existence looks like - and those whom I share space with. I want it to be clear that I am in no way representing the entirety of the queer population's stories or experiences though - and I think that reduces the pressure quite a lot.

It’s very motivating being visible and loud in my art making but I want that to encourage and uplift other voices and perspectives of the queer and trans experience. I suppose, in a sense, my responsibility is to tell my story as authentically as possible.

POL: It’s clear your work is highly personal, documenting the communities that you’re personally part of. This means your imagery also feels very intimate. How do you look at the idea of taking what would have been traditionally seen as “private” moments and displaying them publicly in books/exhibitions?

J: I’m curious by nature and always struggled with arbitrary rules that I couldn’t make sense of. I never understood why we were told our bodies were to be hidden, that we were taught to feel shame in showing or sharing them. I found that keeping bodies and sexuality secretive led to more danger than protection.

I went to Catholic primary school as well and I’m not at all interested in my livelihood being dictated by guilt. I want to feel good about myself, my body and my relationships; whether platonic, romantic, sexual or otherwise.

POL: Through this your work is advocating for representation from different margenalised groups, and includes real people. What does the “right to be seen” mean to you in the photography industry? Where would you like to see change?

J: As a queer, trans Māori artist, representation in the photography industry means more than visibility; it is about authentic and respectful portrayal of marginalized identities. It involves creating spaces where diverse voices are not just seen but celebrated, where our stories are engaged with on both a personal and a profound level. I envision an industry that moves beyond tokenism to genuinely reflect the complexity of our existence, providing opportunities for artists to lead the conversation and shape our own narratives.

“I want to feel good about myself, my body and my relationships; whether platonic, romantic, sexual or otherwise.”

However, circling back to the above question - I’m not here to represent anyone. I’m advocating for queer and trans people to be able to represent themselves, to tell their own stories. I want to create spaces where our voices can uplift each other collectively.

I cop a lot of abuse online - and in the streets - but my mentality is that if I can endure that and speak on those experiences to crowds of people outside of our communities, in the hopes that, that will open peoples eyes to the larger issues - the issues of forced assimilation, respectability politics, the incessant demand from cishets dictating how we are allowed to exist - then its worth it.

POL: You talk about “remembering” a lot in discussion of your work, and are very open about the fact you have a processing disorder that causes difficulty with timelines and distinguishing dreams from memories. We’re really interested in that line between fact and fiction in your work, especially as your images are documentary in nature but filtered through a real personal subjectivity (in what you shoot and how you display it). Can you tell us a little more about how you navigate these lines?

J: Fact Vs Fiction is so subjective! As is the way in which society curates their lives on social media. Every time you’re making a conscious decision to take a photo at a certain angle, to include something or someone in the background, to find your light or use the shadows you're creating an image - there’s no way to avoid that. The idea that this in itself is less truthful bewilders me. No one is falling into this position at the exact moment my camera decides to open the shutter. Everything is a decision, whether conscious or not - and for me, personally, this doesn’t invalidate truths or non truths.

“No one is falling into this position at the exact moment my camera decides to open the shutter.”

POL: There is a poeticism in how you name your projects (for example: Half of my whole life was a dream / The sentimentality of something unseen) what’s your relationship with language and your work?

J: I’ve always been inquisitive in how language is interpreted so individually. Early in my life, around the ages of 5-10, I was an enthusiastic writer and hoped to be an author. Later, in high school, I took a creative writing class and thoroughly enjoyed that too. I like that words can build worlds in a similar, yet very different way, to photography. I want the title to carry its own weight and initiate a feeling of some kind. I want the words to bring together the flow of the imagery - to articulate the essence.

POL: Do you have any influences or artists that have had an impact on your work?

J: Throughout my art making career I’ve been inspired by lots of different things and lots of different people. Two of my biggest, long term inspirations are Nan Goldin and Ryan McGinley: they’re two artists who invite viewers into their worlds, and the worlds of their subjects, so transparently, so authentically; they photograph raw, visceral, sometimes harrowing stories that shed light on their direct experiences.

POL: If time and money was no object what project would you want to do?

J: I’d really love to do a world trip involving collaborations, residencies and exhibitions. I want to travel the world with my cameras, learning what queer and trans existence looks like around the globe. I would then want to compile the images into a book, the videos into a short film and then hopefully travel with those projects again - exhibiting where the works were created to the audiences of collaborators and their family of friends. Fostering communities and celebrating the ever evolving existence of queerness.

POL: What’s next?

J: I’m hoping to make my way over to Europe next year. I’m looking into artist residencies or exhibition opportunities. The past 2-3 years here in Naarm have been very fruitful for my career and I’ve taken advantage of every opportunity I earned here but I want to push myself even further.

A lot of my interest in capturing portraits is so intrinsically motivated by the people I’m spending time with. I’m very interested to see how different things look when I spend longer amounts of time in foreign cities, meeting new people and establishing new connections.

Artist in studio by Jacinta Oaten, 2022

About J Davies

J Davies is a multidisciplinary takataapui artist respectfully doing mahi on stolen lands of The Kulin Nation in Naarm (Melbourne, Australia).

Through ongoing archiving of contemporary queer existence in the city of Naarm, J cultivates connection to community and culture whilst considering themes of identity, intimacy and neurodiversity.

With a uniquely personal perspective; J documents their own life behind-closed-doors and invites their audience and collaborators to collectively contemplate the ways in which we view and value intimacy within our lives.

In 2021 J was diagnosed with a processing disorder that shed light on their difficulty with timelines and distinguishing dreams from memories. In 2022 J published their first book Half of My Whole Life Was Just a Dream which explores the connectedness of consciousness and subconsciousness.