Benoît Jeannet: Wonderful Lie

April 16th, 2021

Swiss artist Benoît Jeannet brings a holistic approach to his image making. From philosophical readings and experimentation, through to innovative installation and display, his artwork disturbs how you perceive reality and exposes the construction that is photography. Through minimalism and beautiful juxtaposition, every one of nature’s gestures is open to be viewed and appreciated. We spoke to Benoît to learn more about his process, inspiration and being aware of the absurdity that’s around you.

POL: First up, can you introduce yourself to our readers and how you would describe your art?

BJ: My name is Benoît Jeannet, I grew up in a small town called Neuchâtel in the French part of Switzerland. Today, I live and work between Berlin in Germany and the Neuchâtel’s area.

I would say that my work takes shape through a polymorphic approach to photography. I have a photographic background and my research is often linked to images and iconography. I use photography as a tool for reflection as well as production. I try to remain as open as possible in the construction of my physical works. I avoid being a slave to the camera, I try to be aware of the form that best suits the research or concept I am developing.

POL: How did you get your start using photography in your work?

BJ: By mistake.

When I was a teenager, I wanted to become a painter but I was too young to apply to a fine arts university. At that time I was doing a lot of vandalism graffiti, I had problems with the police and I had been expelled from high school, so the situation with my parents was quite tense. My mother enrolled me in a preparatory year of art. There was no painting in the program, so I chose the photography option. I started to photograph in the same way I used to do graffiti, I photographed strange urban landscapes at unexpected moments. Then I started a proper photographic education, I developed a strong obsession for the medium and its characteristics.

“Making an image is like doing a puzzle to organise the chaos of reality.”

POL: You use photography in a really interesting way to look at aesthetics. We love your quote that photography is a “great and wonderful lie”. Can you tell us a bit about what this means to you and your photographic style?

BJ: Looking at the globalisation of photography, and the the massive daily production of images, made me think about the responsibility of photographers and artists to make and spread new images. I try to be aware of the power of photography and its specific characteristics to thwart the reality. Making an image is like doing a puzzle to organise the chaos of reality.

In order to build a coherent work I try to evaluate precisely what to show, how and why. Then I can work and play with the medium through simple decisions that will disturb notions of reality, such as questioning gravity or scale.

I try to be conscious of my every gesture to keep control of my work. The relationship between an image and a viewer is usually very direct. So I try to provoke visual disturbances that slow down their reading, to bring the viewer to a second dimension and remind that photographs are constructed things.

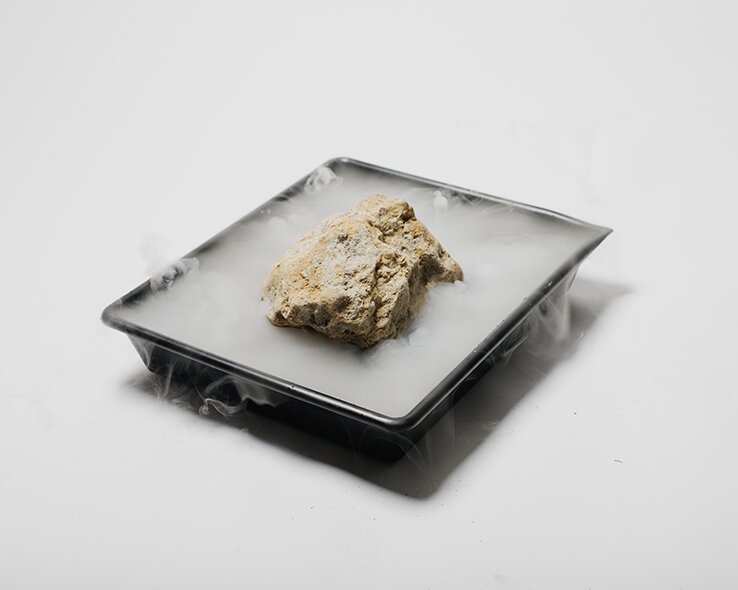

POL: This idea of all photography being constructed is perfectly encapsulated in your project A Geological Index of the Landscape, something that was inspired by Anne Cauquelin’s notion that landscape is an invention. To really look at this notion your landscapes are often fragmented and abstracted, is it hard to disassociate your own eye from pre-conceived notions about imagery when you shoot?

BJ: I think it’s more interesting than hard. I try to be aware of the origins of preconceived notions of certain images, and I work with them. There are inherent elements in the photographs that allow us to identify them and their iconography. So I keep this in mind while making images or objects. It helps me to make decisions but it’s also a way to keep me learning about the history of images and pushing my work and interests in new directions.

POL: Your work is very philosophical in nature, how widely aware do you find audiences are of the different principles you’re exploring in your work? How photography or theory literate do you think people are when it comes to engaging with art photography?

BJ: I am really sensitive to philosophy but I wouldn’t say I have any proper theoretical knowledge about it. I see my work as a tool to observe and think about the movements of the world. The images or material elements of my work are a synthesis of these observations that I’m sharing with different types of audiences.

While working, I develop obsessions on specific subjects that I nourish them through different types of technical, theoretical and philosophical research and experiences. But these are all elements that are part of my work and I don’t expect the viewer to master them to understand my images, quite the contrary.

The theory allows for the correct arrangement of images and objects in space so that a less referenced audience is able to understand and engage them. I think there is a balance that allows you to be precise in what you say without excluding anyone. Then the degree of technical knowledge allows the viewer different depths of personal reading and engaging.

POL: In Where is Mr. X, for example, there is a surreal sense you get when viewing your imagery, even though on the surface it initially looks like documentary photography. The lack of people in the scenes, and the near sci-fi location of CERN, allowing you to swing between documentary and fiction. How do you find the locations you’re going to shoot? What draws you to a particular place?

BJ: Well, it’s quite old work now, but again, photography has a strong relationship with documentary by its nature and history. It’s always a challenge to use a strong reference of reality and succeed through the work to bring it into a singular constructed representation. I’m usually instinctively attracted by objects or locations that escape me, then I work and play in the space between the real document and my personal interpretations of that space.

For this project I managed to become an intern to have access to the location. Then I had a few month to interact with the space and people. Spending three months wandering around a space designed to develop projects that are beyond my capacity to understand made me feel very lonely. So I naturally used this reaction to observe the space with ignorant eyes. The space was thus detached from the applied documentary and migrated to a space that was fertile for potential fiction.

“Absence is a powerful tool, that reminds us of the presence of the frame and the existence of its external elements.”

POL: Why do you choose not to include people in much of your photography?

BJ: I honestly don’t really know. I think it will happen one day but during the few last projects, the human presence was bringing too much of narrative for the purpose of the work.

There are no portraits or people representation in the majority of my images, but humans have an important place in my general work. Absence is a powerful tool, that reminds us of the presence of the frame and the existence of its external elements.

POL: Whilst deeply thought provoking, your work is also very aesthetically beautiful, with a sense of minimalism and playfulness. How would you describe your visual aesthetic?

BJ: I think an image that works should be as clear and simple as possible. It shouldn’t need words, because an image can’t talk. It just shows what’s in it.

A big part of my work is to hide the process of creating it. When I see too many visual effects in a photograph, I just see a way to cover the lack of purpose. I definitely have a “less is more” approach to composition. The challenge for me lies more in how to eliminate interfering elements, rather than in piling on uncontrolled elements in search of a fragile and subjective beauty.

POL: You have a great sense of colour, including a lot of pinks and blues in your images. What attracts you to colour?

BJ: I feel that the colours are connected to intimate feelings, they refer to unconscious personal experiences.

This is something I need and like to see and experience physically. So I avoid theorising my color research, instead I maintain a very personal relationship with it.

POL: You produce work both on location but also in a studio. How has your practice evolved over time?

BJ: I’ve been drawn to the outdoors and the real world for a long time and my practice was close to documentary until 2013. The real world is very chaotic and it is sometimes difficult for me to arrange the elements in a way that fully satisfies me. I moved closer to the studio when I felt the need to construct certain images and arrangements of photographs more precisely. While arranging objects in front of the camera I discovered that sometimes the camera just adds another layer of confusion. My work then began to include installation and sculpture.

My practice is always changing and evolving, I need to take risks and try things to find the form that fits the purpose of my project, or find the purpose that emerges through form. I am always curious and that is a good way to always be learning new things.

I am very attached to photography, but sometimes I need to get away from it to better understand my work outside the medium. I spent the year 2020 doing oil painting and learning chess. I didn’t have any expectations from these experiences, but as I picked up the camera again this year I noticed that my attention is directed to new points; like the importance of gesture, patience or measuring the possible variations.

“My practice is always changing and evolving, I need to take risks and try things to find the form that fits the purpose of my project, or find the purpose that emerges through form. I am always curious and that is a good way to always be learning new things.”

POL: How do you approach creating your pieces?

BJ: I try not to have a recipe in how I approach creating a piece. My work often begins very instinctively. Sometimes I make a few images or a sculpture. From these first elements I try to start a chain reaction that generates a series of pieces that build into a functional whole. I often look for tensions in the relationship between images, objects and space. My works are built slowly because I like to take the wrong path. There is nothing to discover by knowing where you are going, so I avoid shortcuts and try to remain attentive to what surrounds me.

POL: The way you display your art is also incredibly interesting and contemporary. Your work isn’t necessarily hung on walls in a traditional way but, for example at La Fabrik, is part of an immersive art instillation. How important is how works are displayed to how we understand their meaning? What draws you to this more creative exhibition design?

BJ: I avoid being a slave to the traditions of the medium. I find it really important today to be aware of the status we give to images: transposing an image into an object modifies the relationship between it, the space and the viewer. This allows me to build new reading grids based on material references and to establish a spatial connection between the different pieces. This is especially true in my project, Escape From Paradise, in which I worked a lot with images and the relationships between photographs and objects.

The photograph is obviously in two dimensions if one stops at the representation. But a photograph exists only through its material support. Taking into consideration the spatial and physical dimension of a photograph offers additional working tools. Sometimes the format is sufficient and sometimes it is necessary for me to pierce representation and give the image another form.

“Transposing an image into an object modifies the relationship between it, the space and the viewer. This allows me to build new reading grids based on material references and to establish a spatial connection between the different pieces.”

POL: There is a sense of humour to your work, an underlying absurdity, how important do you think this is for a contemporary artist and photographer?

BJ: I guess my work is an extension of the way I perceive the world and it’s true that I am very receptive to its absurdity. I like to work with contrasting notions and I like to point out an absurd paradox when I catch one, but I never really make jokes through my work. I like to be able to laugh a bit while working seriously.

In general, I think humour is a great powerful tool that I also love as a viewer. I think it must be natural, the work of Roman Signer or Fabian Boschung are examples of the perfect balance in my opinion.

POL: If time and money were no object, is there a shoot or a project you would love to do?

BJ: I have plenty of them! The last one I have in mind would be to make a piece made of thousands of unscratched Lotto tickets. I’d like to make an itchy artwork.

“Taking into consideration the spatial and physical dimension of a photograph offers additional working tools. Sometimes the format is sufficient and sometimes it is necessary for me to pierce representation and give the image another form.”

POL: What are you working on now? What’s next for you?

BJ: With the current global situation, I spend a lot of time in the studio. I’ve built a body of work around the relationship between images and objects, which I’m trying to unravel through research and experimentation, so we’ll see where that takes me.

The future is very uncertain these days. I’m currently working without a gallery or agency so it’s hard to make plans. But I would like to make a book out of the Escape From Paradise work and I would love to have a new work to project for exhibitions when the pandemic calms down.

“I’d like to make an itchy artwork.”

About Benoît Jeannet

Benoît Jeannet was born in Born in 1991. He lives and works in Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Benoît Jeannet graduated from Vevey Photography School (2012) and then from the ECAL University of Art and Design in Lausanne (2015) and holds a master’s degree in visual arts from HEAD Geneva University of Art and Design (2019). He was awarded the Broncolor Light Award at Vevey’s Festival Images in 2019 for his series Escape from Paradise. His work has been shown in numerous exhibitions in France and abroad, including at the Festival Images, Vevey, Jimei × Arles Photo festival, Jimei (China), Foam Museum, Amsterdam and the Rencontres de la photographie, Arles.